- STAR⟡MAIL from HALOSCOPE

- Posts

- Savage Beauty, revisited

Savage Beauty, revisited

Liv Elniski on Lee McQueen’s controversial 1995 collection.

Kilts, provocation, and tailoring as story-telling.

This week for STAR⟡MAIL, Liv Elniski on Lee McQueen’s controversial 1995 collection, “Highland Rape”.

Liv Elniski on Lee McQueen’s controversial 1995 collection, “Highland Rape”. You can read more from Liv on the Substack Victorian Secret.

CONTENT WARNING: Discussion of sexual violence.

Lee McQueen’s “Highland Rape:” Scottish Tartan and Depictions of Violence on the Catwalk

by Liv Elniski

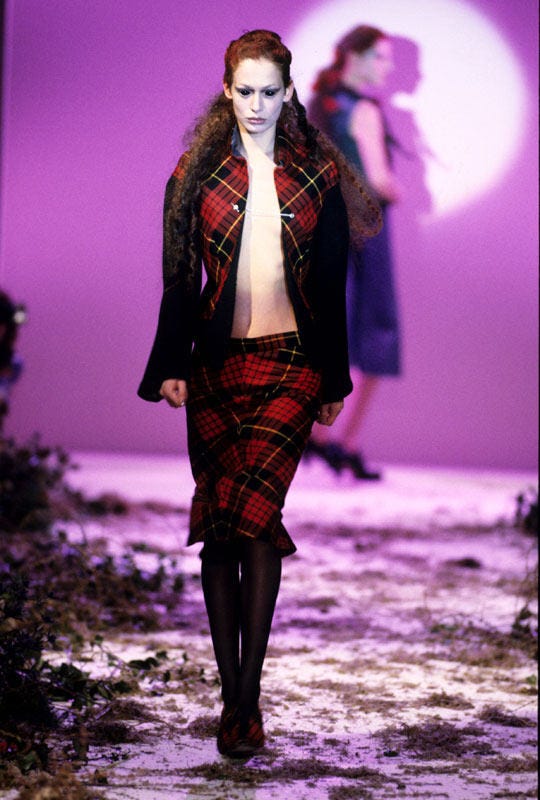

Fig 1. Alexander McQueen, “Highland Rape,” Fall/Winter 1995/96. Via: Vogue

The late Lee Alexander McQueen’s fifth complete collection post-graduation from London’s esteemed fashion school Central Saint Martin’s, was staged on March 13, 1995 at London Fashion Week, with the financial backing of the British Fashion Council.

The runway, strewn with heather and bracken, set a haunting stage as models walked with hair styled in both cropped, pixie cuts and carmine locks trailing down their spines. The almost-nude women with blacked-out contact lenses made their way down the runway, some even appearing lost, confused, or scared. The models' walks showed little consistency, with some staggering, some walking traditionally, and some marching like soldiers. A dissonant soundscape, featuring loud clanging, thunder and wind, house music, and the occasional siren, charged the atmosphere around the designs. Many of the models smiled flirtatiously, as fashion historian and scholar Caroline Elenowitz-Hess put it: “blurring the line between horror and allure.” The now highly controversial collection entitled Highland Rape, evoked terror and unease among the 1995 London Fashion Week audience.

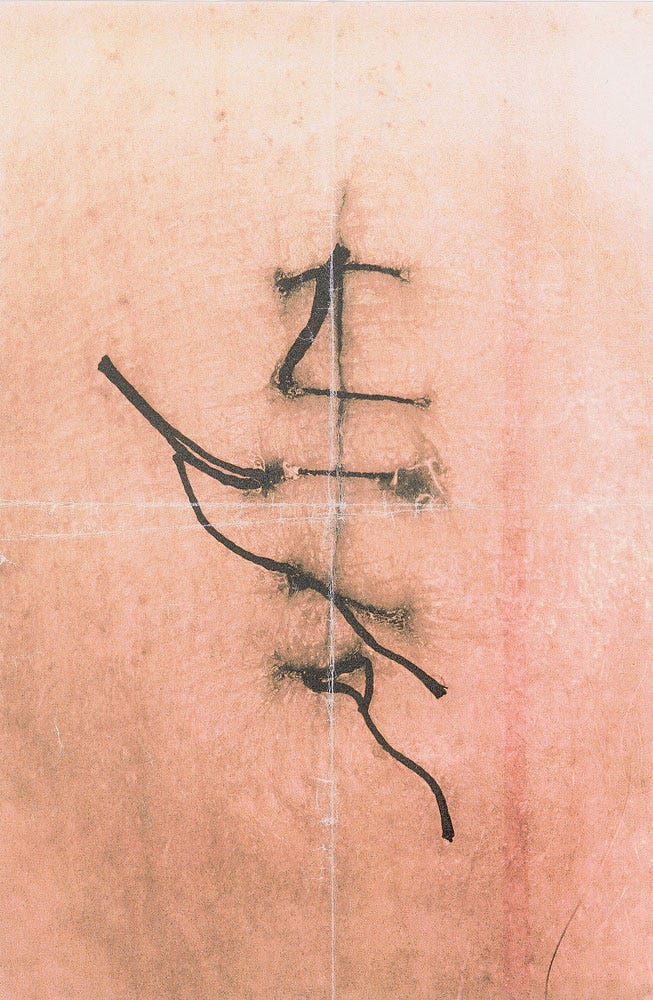

Fig 2. Alexander McQueen, “Highland Rape,” Fall/Winter 1995/96, Via: The Metropolitan Museum of Art “Savage Beauty” 2011

Fig 3. Alexander McQueen, “Highland Rape,” Fall/Winter 1995/96, Via: The Metropolitan Museum of Art “Savage Beauty” 2011

McQueen stated that his inspiration for this collection stemmed from his Anglo-Scottish heritage: his father was a Scottish taxi driver, and his mother, an English school teacher. Reflecting on the collections theme McQueen mused, “I’d studied the history of the Scottish upheavals and clearances … Highland Rape was about England’s ‘rape’ of Scotland.” Here, McQueen is making reference to his learning about the Jacobite Rebellions otherwise known as the Scottish Clearances of the 17th and 18th centuries. The Jacobite Rebellions were a series of uprisings and wars in Ireland and Britain between 1688 and 1746, aimed at restoring the House of Stuart to the British throne after the deposition of King James VII of Scotland. At their core, these rebellions aimed to return the exiled Stuarts dynasty to power in Ireland, Scotland, and England. During the final culmination of events, the Battle of Culloden, thousands of innocent Scottish civilians living in the Highlands were killed and imprisoned (McQueen would later dedicate his collection Autumn/Winter 2006 to this specific event). These historical events signaled both the death of the traditional way of life in the Scottish Highlands, as well as the rise of the centralized state of Britain.

Fig 4. Back stage of Alexander McQueen’s A/W 2006 “Widows of Culloden” models pose before heading on stage. Photograph by Robert Fairer. Via Alexander McQueen: Behind the Scenes

Notes on Tartan & it’s Historical, Cultural Importance

Tartan is a patterned cloth traditionally made from wool, each logged and categorized in the Scottish Register of Tartans. The word sett describes the distinctive pattern of a tartan: the sequence of colored threads, which form a symmetrical, repeating, often geometric pattern. Breacan is the Gealic term for the original form of a tartan garment, before the use of tailoring to create a kilt, the garment that today is most closely associated with the textile.7 Contrary to popular belief, setts do not have any directly traceable links to Scottish families or clans. This association with clans emerged from nineteenth-century writings by historians, as well as tailors, and woolen manufacturers.

According to scholar Fiona Anderson, tartan has “powerful connections with often romanticized notions of Scottish identity and history.” Although the precise origins of this cloth are unknown, a fragment found in Falkirk, a town in the central lowlands of Scotland, dating back to the third century C.E. suggests that it has existed in the country for over one thousand years. Another one of the oldest fragments of Scottish tartan, discovered in a bog in the early 1980s, which dates to the sixteenth-century, resides at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum.

Fig 5. Cloth (Fragment), found at Falkirk, Stirlingshire, (Buried around 230 AD). Edinburgh, UK: The National Museum of Scotland, 000-100-036-743-C.

However, what we now associate with the word tartan, complex patterning, and colors, did not exist before the early sixteenth century. Hugh Cheape, author of Tartan, the Highland Habit writes, “the word ‘tartan,’ probably French (from the word ‘tiretaine’), was in use early in the sixteenth century.… It seems likely that in some way that we can't now trace, this word came to describe the fabric we now call tartan.” By 1600, tartan was established as an element of popular culture in the Highlands, widely worn by all members of society, becoming a distinctive element of Highland dress. The plaid print, otherwise known as breacan, is its most distinctive feature. This textile was adopted by Highland women as a shawl and belted (as a skirt-like style) by Highland men. Scholar Archie Brennan states that “Up until the eighteenth century, the setts worn were largely determined by the locality and tastes of the weaver and purchaser.” Around this time, the kilt as we know it in its tailored form emerged as a style in the Highlands (see Fig 6).

Fig 6. William Mosman, “The Macdonald boys,” (about 1750). Glengarry Heritage Center. 49197

Prince Charles Edward Stuart encouraged elements of Highland dress such as tartan to be the uniform for the Jacobite army in the events of the seventeenth century, thus creating an association with political rebellion and sedition. The result of this was the Dress Act of 1746, otherwise known as the “Disclothing Act,” which stated:

No man or boy within . . . Scotland, shall, on any pretext whatever, wear or put on the clothes commonly called Highland clothes (that is to say) the Plaid, Philabeg, or little Kilt, Trowse, Shoulder- belts, or any part whatever of what peculiarly be- longs to the Highland Garb; and that no tartan or party-colored plaid or stuff shall be used for Great Coats or upper coats, and if any such person shall presume after the said first day of August, to wear or put on the aforesaid garments or any part of them, every such person so offending . . . shall be liable to be transported to any of His Majesty’s plantations beyond the seas, there to remain for the space of seven years.11

This law made donning a kilt a criminal offense, punishable by imprisonment or forced transportation. Although it did not ban the use of tartan, it restricted its use for upper coats and jackets. Post-Culloden, the British government’s sumptuary laws aimed for the suppression of Highland identity, through the banning of wearing Highland dress.

McQueen’s Interpretation and Application of Tartan: Building a Historical Design Narrative

The opening looks of the collection established key stylistic elements that would recur throughout McQueen’s career: hobbling pencil skirts alongside 1950s-inspired cinched-waist circle skirts, ankle boots, and heels featuring strange cut-outs, and garments designed to elongate the limbs and torso of the wearer. The collection relies heavily on the prominent use of tartan as a touchstone for his historical narrative. The “MacQueen” tartan, registered in the Scottish Register of Tartans, characterized by black, red, and bits of yellow, is utilized in a variety of garments throughout the collection.

Fig 7. MacQueen Tartan. Via: The Scottish Tartan Registry

On the runway, tartan first made an appearance about halfway through the production, in the form of an unfastened, short-sleeved, frock coat inspired, outerwear piece worn atop nothing but the model’s bare breasts. A long-haired model donned a sheer, lace top paired with wide-legged tartan trousers. The following look, a tartan pencil skirt, with a silver chain dangling from the crotch area of the wearer. Other garments include a peplum top, pencil skirts, an empire waist dress, and even a pair of red tartan panties.

McQueen’s use of the textile departs radically from its applications in traditional Scottish dress, both in terms of garment construction and aesthetic intent. Rather than serving the conventional function, tartan in this collection is employed as a symbolic device, interrogating ideas about national identity, heritage, and rebellion.

Fig 8. Alexander McQueen, “Highland Rape,” Fall/Winter 1995/96. Via: FIT Library Designer files.

Fig 9. Alexander McQueen, “Highland Rape,” Fall/Winter 1995/96, Via: MJ Dorian

Fig 10. Alexander McQueen, “Highland Rape,” Fall/Winter 1995/96, Via: The Metropolitan Museum of Art “Savage Beauty”

Critical Responses to Highland Rape

Marked by an aesthetic of violence against women, Highland Rape has become one of McQueen’s most frequently criticized collections, with many journalists and scholars claiming that the designer used “rape and violence as a form of entertainment.” In the immediate aftermath, most major fashion publications condemned McQueen, and rightly so. English journalist Sally Brampton of The Guardian questioned McQueen’s talent, describing the collection as “a sour note,” saying “it is McQueen’s brand of misogynistic absurdity that gives fashion a bad name.” The Independent published a review entitled “The Emperor's New Clothes,” describing the show as a “sick joke.” The collection review goes on: “To admit to not liking his collection is to admit to being prudish. So, we admit it. He is a skillful tailor and a great showman, but why make models play abuse victims? The show was an insult to women and his talent.” Though I do feel that this review is a bit harsh in its delivery (especially for a designer early in their career, this collection certainly did not undermine his ability to execute technically skilled, imaginative garments), the writer’s frustration with McQueen’s portrayal of violence against women is understandable and valid, especially given McQueen’s position as a male fashion designer.

When asked about the public’s response to the collection, Lee responded angrily to criticism that the collection was a shout-out against his peers: English designers, producing “flamboyant Scottish clothes.” He told Women’s Wear Daily in 1995, “Everybody thinks it’s all about pretty tartans and heather. But I wanted to show that the war between the Scottish and the English was essentially genocide.” He most prominently called out female British Designer, Vivienne Westwood, which surely does not help him in defense of accusations of misogyny.

Fig 10. Vivienne Westwood, Fall 1993 Ready to Wear. Via: Vogue Runway

Despite being on record multiple times stating that the inspiration for this collection was the seventeenth-century Jacobite Rebellions, and the subsequent eighteenth-century Scottish Highland clearances, McQueen is arguably not the most reliable narrator. He also made mention of other sources of inspiration for his 1995 collection: the designer more than once alluded to witnessing the abuse that his sister suffered at the hands of her ex-husband. Famously, McQueen once said in a Vogue 1997 interview, “I want to empower women. I want people to be afraid of the women I dress.” McQueen had the tendency to speak about his work in a stream-of-consciousness format. Nick Knight's collection of interviews with fashion designers on his platform ShowStudio are highly valuable in that they provide a plethora of these quick, rash answers given in moments of vulnerability. When this is taken into account, it is difficult as a viewer of his work to believe that the historical narrative was truly the only primary source of inspiration.

McQueen would state for years to come that his design ethos was one of making women appear fierce and herculean, motivated by his deep-rooted admiration for the women in his life, notably his sister, mother and dear friend Isabella Blow. This response, according to Elenowitz-Hess, “fails to take into account the visual language of the garments themselves and how the performance fits into representations of sexual violence.” Whether or not McQueen possibly had unconscious design motivations tied to familial trauma, the generally theatrical nature of the violent imagery complicates his professed aim of empowerment and a historically informed narrative. The collection’s staging, featuring torn garments, which expose the genital area of models bound in restrictive styles, and an aggressively choreographed runway show, walked a very fine line between spectacle and subversion (see Figure 11). As Elenowitz-Hess muses, ignoring the performative and symbolic elements of the garments themselves risks reproducing a dangerous narrative of violence under the guise of female empowerment. Looking at Highland Rape in this light, McQueen’s work becomes a sight of great tension, something which would follow him through his career, until his untimely death.

Fashion journalist Tim Blanks describes Highland Rape as an “image-building exercise,” pointing out that none of the garments displayed in the collection ever went into production or reached store shelves. The non-commercial nature of this show is probably in part to thank for the obvious play at provocation. Although the collections prominent use of tartan made nods at Scottish identity, the collection is unified by its sharp, angular precision of tailoring, a defining hallmark of McQueen’s legacy among his contemporaries.

Despite McQueen’s stated intentions, much of the critical discourse surrounding Highland Rape has centered on its perceived exploitation of women’s trauma rather than the historical exploitation of Scotland by England, which the collection was ostensibly designed to comment on. The sexually violent nature of the clothing- torn dresses, exposed bodies, in combination with the intense staging of the runway which models stumbled down appearing violated, overshadowed any political or nationalistic message. McQueen’s theatricality, though undeniably potent, muddies the water between critique and complicity. Unfortunately, in the end, the spectacle seems to have dulled the garments potential to reshape public understanding of historical violence, reducing it to an aestheticized shock.

As an admirer of McQueen’s work, I am no stranger to his many provocative statements about fashion’s ability to make women appear strong and intimidating, to “arm them” against predatory men. But it does strike me as concerning that in order to believe his designs hold this power, he feels that women's clothing have an impact on whether or not they are abused or violated. This logic risks veering into dangerous territory, echoing victim-blame ideologies. While McQueen always attempted to frame his work as empowering, often times his work relied heavily on the same tropes of violence and violation he claimed to be attempting to subvert.

This is not to say that his work is not brilliant, and singular. I truly believe that Alexander McQueen is one of the greatest fashion designers in modern fashion history. However, his brilliance does not absolve him from critique. In a moment of male-creative-director-musical-chairs, I am considering the importance of female design perspectives in an industry which has historically, and is currently dominated by men. I find myself increasingly attuned to the limits of male authorship, particularly when it comes to representing the female experience through art and design. Recently, online discourse around said “musical chairs,” has highlighted how few women hold the reins of narrative power in this industry. Even gay men who deeply admire and love women are not immune to misogyny.

“Highland Rape,” A/W 1995/96 Invite/Back stage pass. Via RR Auctions

Like so many fashion topics, Avery Trufelman did a great episode on this history of tartan and plaid:

An archive of the guided tour audio from The Met Costume Institute's May 4–August 7, 2011 exhibition: Alexander McQueen Savage Beauty

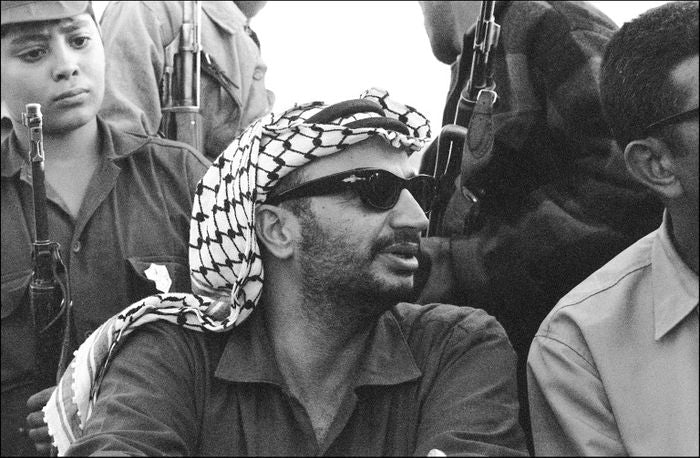

When discussing the colonial violence of the Scottish Clearances of the 17th and 18th centuries and the way that the Disclothing Act criminalized protest of that violence, it is hard not to draw a comparison to what is happening right now to the Palestine people in Gaza. In honor of the powerful symbolism of textiles with rich heritage like tartan, read bout the history of the keffiyeh and shop this Palestinian family owned brand: