- STAR⟡MAIL from HALOSCOPE

- Posts

- Textiles and technology have always been interwoven.

Textiles and technology have always been interwoven.

See what I did there?

What do a 1950s IMB computer and a 19th century jacquard loom have in common? Both machines were both fed digital data coded onto punched cards. When it comes down to brass tacks, knitting and crochet instructions are written in their own form of code as well. In a truly symbiotic way, you can trace the roots of the technology behind the cutting edge smart-wearables and hi-tech garments being devolved today all the way back to data processing systems developed for textile production centuries ago.

This week, I had the delight of interviewing Dr. Kadian Gosler, a luminary figure in the realm of lingerie design and research. I’m so excited to share with you her insights into the cutting edge of wearable technology, adaptive design, and additive printing production. Oh, and her 3D printed lace designs are beautiful!

Tech and Textiles

Dr. Kadian Gosler is a luminary figure in the realm of lingerie design and research. You might be familiar with her high-tech lingerie designs made with 3D-printed lace. Gosler’s fascinating research ranges from the development of e-textile bras for marginalized mature women to the history of the sports bra.

Check out her newly launched research and design atelier, KDN R&D Atelier!

Your research into the futures of Bra Wearables technology focuses on aging women of marginalized identities. In what ways would this population benefit from smart/interactive wearable bra technology?

My research started with my interest into Bra Wearables, a subsect of “smart bras” inclusive of mechanical, electrical and chemical components. I employ the term Bra Wearables as current marketing has watered down and distorted the original term smart bras. For a bra to be considered smart it should be able to react to stimuli. After examining the Bra Wearables state-of-the-art, I found there are several subfields with products being developed for preventative health, sports & fitness, body enhancement, physical safety and more. The thing that became clear was that many of these concepts were being pushed from a technology perspective without wearer input or understanding wearer experience. One of my favourite examples is the “Emotional eating bra” (2013) by Microsoft, University of Rochester and University of South Hampton [IMAGE 1]. They developed a bra that would signal to the wearer they were stressed and overeating. Of course, this did not go down well with many women who highlighted its sexist undertones. As someone who is an emotional eater - I certainly don’t want my bra to be the bearer of such news.

Continuing, realising that there was minimal research, in Western academia, on lingerie and ageing women, I concluded that was the group to focus on. Mature women are invisibilised in fashion and even more so in lingerie. I can tell you the last time I saw a mature body in lingerie advertisements because I seek them out. However, when was the last time the average shopper did? Mature and older women have worn bras for a lot longer and have embodied knowledge that would be beneficial to bra designers. Additionally, mature women are going through a huge shift where they are being pushed out of the work force, potentially going through menopause, taking care of ageing parents and children, and so much more. Consequently, they become the best target group to develop health and wellness fashion-based technology with.

A mature lingerie consumer experience online questionnaire was deployed during my PhD thesis, March 2019. The questionnaire was intensive having three parts with the last focused on Bra Wearables. Overall, the data shows this group is interested in bra wearables that are health and wellness based, i.e., detects/monitors heart rate, stress detection and relief, sexual wellness and such. The issue arises as a large majority do not believe the bras will perform to a high standard, be comfortable, or fit adequately. Thus, by bringing the wearers into the design process many of these issues can be properly investigated and designed for. I believe bringing together fashion and health for this target group would be revolutionary as society can begin to put resources into truly understanding women’s health and various needs.

Separately, because mature wearers are the focus of newly designed concepts does not mean the concepts are not beneficial to others. A stress relief bra designed with mature women would still benefit collegeaged wearers, the potential issues would be aesthetic and fit.

Much of your work focuses on designing garments for wearer experience. How do technologies like 3D printing enable you to design clothing with the experience of the wearer in mind? How do you balance utilitarian and aesthetic driven aims in your work?

The future of sustainable and technologically advanced fashion, including lingerie, depends on centring the wearers experience within the design and development process. As documented in my thesis, wearers clothing experience is complex and informed by socio-cultural, psychological and physio-affective factors. Therefore, design teams need tools and frameworks for guidance in their approach. My thesis provides an interdisciplinary bra wearing framework, expanding on the aforementioned factors, which can be adapted and applied to other clothing. The framework allows design teams to better identify the wearers needs and design requirements. Moreover, tools such as, ‘Experience Map’, borne from the interaction design field, enables design teams to focus on the numerous aspects of garment experience like tactility, texture, visual, smell, etc., which are essential to centring the wearers experience. Lastly, and possibly the most important, is centring the wearers experience requires empathy throughout the design process. Here empathy is active and that means identifying with and understanding the wearers perspective through various techniques such as role-playing. Role-playing in the academic sense means embodying the wearer to deepen understanding. To comprehend the challenges of a bra wearer with arthritis in the hands, the design team might utilise creative means to stiffen their hands and attempt to don and doff a bra to understand barriers faced. This is particularly useful if the design team doesn’t have direct or limited access to participants, or if information is lacking after interviews or workshops as discussing intimates can be a sensitive subject.

IMAGE 2, IMAGE 3, IMAGE 4, IMAGE 5

A good example of designing with the wearers experience in mind is the world’s first smart fully 3D printed posture correcting bra developed in 2024 [IMAGE 2,3,4 and 5]. The bra concept was borne out of a wearers’ social media post on their bra causing them back pain. As it’s not something I’ve experienced, empathy was essential in my approach. Through research on breast weight, upper body pain, psychological effects, and the significance of proper posture the design idea grew. The Experience Map was quite valuable in delineating the requirements for the bra and potential wearer experience. The bra needed to look appealing, comfortable, and functional. Thus, a lot of the traditional lingerie knowledge was necessary to approach 3D printing the numerous elements keeping in mind the texture, tactility, shape and more. The final product ended with a modular 3D printed bra with removable racer back that houses the hardware, including the vibration sensor that provides gentle biofeedback encouraging posture mindfulness. The next step is wearer trials, nevertheless, a well-fitted bra with the smart posture application has the strong potential to alleviate back pain.

What drew you to 3D printing as a mode of lace making? How do the process and produced textiles differ from lace created in traditional methods? What are the limitations and what is gained?

Image 6, Image 7, Image 8

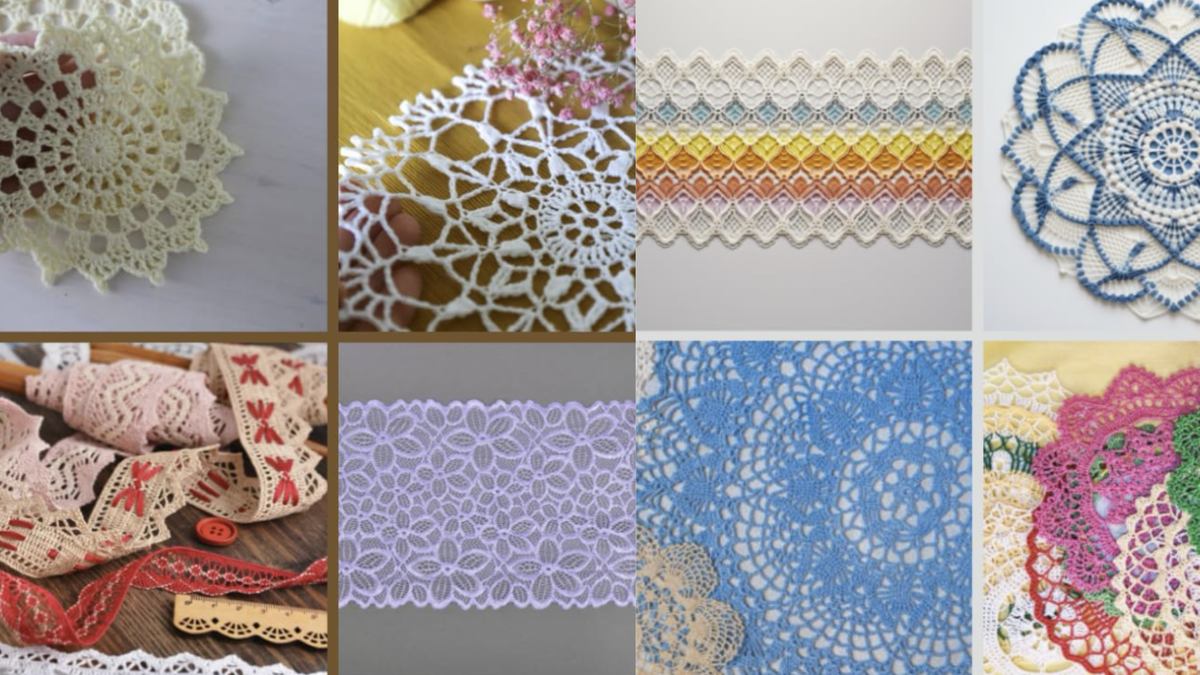

As a lingerie designer, I’ve always had a relationship with lace which started early in my undergraduate studies at the Fashion Institute of Technology. I’m fascinated by the level of detail and intense emotions it evokes as it can transform a simple piece into art. Lace varies in texture, weight, and form providing such myriad possibilities. If anyone has seen pieces by Solstiss and Sophie Hallette or visited the Lace Centre & Museum in Brugge [IMAGE 6], then it would be pretty clear why I appreciate the art form. Once I began experimenting in mid 2020 with 3D printed bras it was a natural evolution to explore and incorporate 3D printed lace to elevate the pieces [IMAGES 7 & 8]. That exploration deepened my understanding of the design process for 3D printed lingerie.

Image 9, Image 10 (©2017, Lisa Marks.)

To be clear, I am not a lace expert so I cannot properly provide justice to the ways traditional lace (bobbin, needle, crocheted, knitted, cutwork, etc.,) is designed and produced. One of the goals in launching KDN Research & Design Atelier is to continue research in this field potentially collaborating with traditional lace designers to extend knowledge in this area. Nevertheless, as a 3D printed lace expert and researcher, I can highlight how the process differs when designing and developing a 3D printed lingerie concept. It’s essential for people to understand the materials are naturally different, therefore they will behave and have differing hand feels. Traditional lace can be made from a variety of materials i.e., silk, cotton, polyester, wool, rayon, etc. On the other hand, flexible 3D printed lace is currently made from Thermoplastic Elastomer (TPE) or Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) which are amalgamations of plastic and rubber [IMAGE 9]. Both traditional and 3D printed lace begin the same, whether through hand or computer-aided design. They differ in the next steps, with 3D printed lace moving into a program capable of 3D modelling objects such as Rhino. This is a bit similar to machine laces which uses embroidery software to virtually preview the lace before moving into stitch planning. After the 3D printed lace sample is further developed in Rhino, i.e., defining peaks and valleys, reshaping certain facets, then it is saved in a file format allowing for it to be sliced and printed. I’ve skipped a number of steps as the process is intricate, but essentially the designer is prepared for the iterative trial-and-error nature of 3D printing with flexible filaments. Another approach is to use Rhino and Grasshopper to design parametric laces using algorithms, resulting in complex patterns unattainable by traditional methods [IMAGE 10].

Image 11, Image 12, Image 13

So far, 3D printed lace is limited only by creativity [IMAGE 11, 12, & 13]. I’ve had to reflect many times on this. If the aim is to copy and try to replicate exactly what traditional lace has already achieved, then one can easily list off the limitations of 3D printed lace. However, if the goal is to experiment on its potentials, then the options are “limitless” with the help of filament manufacturers providing more options in softer shore hardness, textures, properties, and colours. With that said, there are obstacles to overcome in 3D printed lingerie. For example, while some of the flexible filaments are antimicrobial, antifungal, with high tear and wear resistance, they tend to be hygroscopic which may eventually degrade the garment. More research is certainly needed in the wearing experience and longevity of 3D printed lingerie.

To end on a positive note, with 3D printed lingerie we have the potential to design customised pieces, evolve the ways we design functional bras, create sustainable and eco-friendly pieces, extend garment life while possibly bringing back passed-on heirlooms. I’m highly excited for wellcrafted pieces to be passed down again.

Handmade bobbin lace is an extremely time and labor intensive good, which has historically been produced by poor women from Sri Lanka to Northern England to Brazil. As a woman designing and making lace yourself, what does using additive manufacturing and producing this work in a traditionally male dominated STEM field mean to you?

I’ve only recently begun to think of myself as being a part of the STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Math) field. Maybe it’s because I approach the work I do from a fashion, particularly lingerie, perspective. As I merge traditional fashion techniques such as draping and pattern making with programs like Rhino and Arduino used in the STEM fields, I’m moving beyond the hard drawn lines into this amorphous hybrid space. My supervisor would call me a hybrid designer due to my ability to mix fashion and tech, as well as, industry and academia. As a Black woman, I am often an outlier both in fashion and tech. Therefore, I find that I have a unique perspective and distinct advantage point which is a good thing as the technology isn’t my primary goal.

Image 14, Image 15, Image 16

A funny example, most people begin additive manufacturing working with stiffer filaments like PLA or ABS on FDM machines. As a lingerie designer I no doubt want materials that are soft, flexible, breathable and comfortable against the body. So, I jumped right into working with TPE and moved on to TPU [IMAGE 14, 15 & 16]. Once it came time to working with stiffer filaments, I was a bit lost on settings and best practices. Asking a friend for assistance, they laughed and said you could teach on using some of the most difficult filaments like NinjaTek Chinchilla with a shore hardness of 75A but you’re clueless on the easiest filament to print.

Interestingly, I see this also in 3D printing communities where it’s male dominated. I get really positive feedback as they are amazed at the creativity from a fashion point and fascinated by the usage of soft flexible filaments creating genuinely wearable and comfortable pieces. And I’m astonished by what they achieve using PLA and paint!

It’s really a great way to show the different perspectives that are needed. Truthfully, I find it exciting.

On the topic of early computing, Ada Lovelace is famously quoted as saying that “the Analytical Engine weaves algebraic patterns, just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves.” The punched cards used to program Jacquard looms with weaving patterns were adapted as a method of programming early computers. In your work, you also find connection between textiles and technological advances. Do traditional modes of lace construction influence your 3D printed design work in this same way, or are you more interested in utilizing this technology to produce lace that could not be feasibly crafted with bobbin and thread?

Image 17 (Portrait of a lady, by William Larkin before 1613), Image 18

Traditional and historical lace aesthetic influence my 3D printed designs more so than traditional modes of lace construction. During my early 3D printed lace explorations, I would examine artistic exemplars of lace seen in Renaissance and Baroque paintings. Thus, the goal was replicating the aesthetic which produces similar pieces [IMAGE 17 & 18]. Similarly, I was influenced by the finished aesthetic of Tatting and Hardanger lace which I was able to replicate using 3D printing [IMAGE 19 & 20].

Image 19 (Source: @Hardangerrebel on Instagram), Image 20

To 3D print lace with the aim of exactly mimicking traditional lace construction to produce replicas, outside of the realm of research, begs the question why? Many might say faster production. And to that again I ask why? Faster production to produce more products isn’t necessary. As someone aware of the pitfalls in the manufacturing industry and its linkage to over-production and wastage, I for one hope 3D printed fashion does not follow that trend. Instead, it’s an opportunity to slow down and create quality well-crafted garments. Many might not be aware, but both the bra and lace industry have an intertwined history with technology owing to their continuous evolution. My interest in this area is to recreate traditional lacework utilising new materials which has potential to preserve the craft, while also expanding on the creative possibilities and redefining the definition of lace – evolving the lace and bra field.

Image 21 (Border of Genoese bobbin lace, Italian, 1600-1629, Victoria and Albert Museum, Textiles and Fashion Collection), Image 22

Scammers are using AI to write nonsensical instructional book about lacemaking:

Some coverage of tech on the runway from last year’s NYFW:

Crystal Bennes' fiber art instillation of hand-woven jacquard wall hangings created from translating cern computer punch cards into jacquard weaving instructions:

“There are any number of tedious tech articles on the relationship between Jacquard’s punch card-based mechanism and Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine that proclaim Jacquard’s genius and embrace him as inventor of the first proto-computer. That said, when I happened upon the cards at CERN, the connections between histories of computational and weaving technology were too generative to ignore. Not only were there parallels between sexism in physics and technology, namely, the erasure of women and people of colour from conventional histories that tend to glorify white male figures. But there were also correspondences between the use of gendered, sometimes ‘low skill’ labour—women in weaving as pattern readers; women in physics as “computers” or “scanner girls”—and the later evolution of such gendered work into labour-saving computerised algorithms.“

When Computers Were Women, 2021

four hand-woven Jacquard wall hangings made of recycled cotton, organic cotton and lambswool, 70cm x 300cm each